| view Scribd version (PDF) | |||||

Castings: A Conversation With Deborah Margo (DM), Bianca Scliar Mancini (BM) and Janita Wiersma (JW)

When we first invited the artist

Deborah Margo to contribute to this issue of

Inflexions, the proximity between the concerns raised in her works

and our own practices motivated us to embark on the conversation you

read here. Rather than conducting our curiosities through

a traditional “question and answer” format, we developed a

structure in which blocks of ideas were exchanged between the three

of us, developing a flow of conversation that allowed us to trade projects,

references and questions. What we share here is a compilation

of this process, which occurred over the course

of three weeks. Materiality JW: What

first drew me to Deborah’s work were the site-specific Light-Earth

Drawings made in a stairwell at Mount Allison University in Sackville,

New Brunswick. The drawings were so slow and unobtrusive that

they had to be looked for and, once found, there was a desire to catch

the light and drawing in alignment. I felt myself as a third in

the space between passing light and physical trace. Usually when

using the stairwell I would simply pass through it, but encountering

the deliberate marks on the wall, I felt myself moving with it.

The shape of the windowed stairwell, the tall casings, the expansive

space of the architecture was asserted into my field of movement as

a subtle choreography. I felt the flow of traffic, which

was the light recorded, enter the space and be mirrored by the moving

bodies. In this work, I felt time shaped by Deborah’s pigment.

The passing lights move on even as they are recorded, embedding a feeling

of pastness to the present looking. Something was once there,

the artist has left me proof – but the traces are not conclusive. I am sharing with

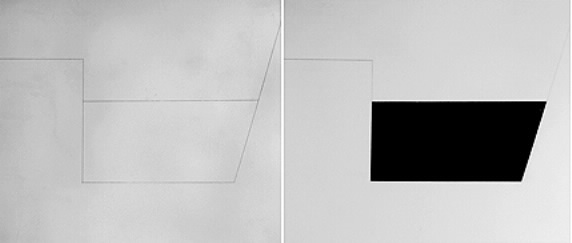

you both some images from Spacious Object, a show I had recently

at Galerie Les Territoires in Montreal, Quebec. With this work

I was aiming to create abstracted fragments of things seen: fields,

concrete structures, shadows, ripples on water. What I was looking

for in each piece was a feeling of spaciousness and time slowed down

in the traces of what was, much as I felt it in Deborah’s Light-Earth Drawings. Abstraction is a way for me to slow the process

of recognition so that the exchange between viewer and viewed has a

chance to develop. Reservoir 2 and Reservoir 3, Intaglio etchings, 14x13”, Janita Wiersma, 2009. Fragments, cast concrete and plaster, approx. 12x12”, Janita Wiersma, 2010. DM: Many

thanks for your sensitive writing about the Light-Earth Drawings in Sackville. Where to begin?

First off, nothing is immobile. Everything is constantly changing -

whether we notice it or not. Art making can be a way of trying to slow

time down for oneself or to at least attempt to be aware of its intransigence.

Potential movement? As the recent earthquake in Ontario and Quebec reminded

many people, rather it is our perception of the constancy of movement.

We tend to want to believe things can be at a standstill, but they aren’t,

even when you are stuck in traffic and it appears nothing will ever

change. Light too, is

constantly changing, shifting. The light interventions have been about

recognizing this and the puny attempt to fix it in a drawing, while

knowing its patterns have already moved on to other configurations.

Movement becomes much larger than what I have traced; sun, earth axis

and turning. I have paper forms of some of the shapes the sun has taken

as it passed through a window and made patterns on the floor, made in

Sackville many years ago. I’ve wondered what would happen if I made

them into solid forms and then placed them in a space without windows

(a typical gallery situation). They look like these modernist configurations;

cast in concrete they would take on a further muteness (as in dumbness),

but yet they derive from something so alive and fleeting. Roland Poulin’s

early concrete works appeal to me for the same reasons, far from the

drama of so much of his more recent work. BM: Deborah,

I see you less as a collector than a provoker of set-ups, challenging

the materials to respond to the ‘chemical’ or physical encounters

you propose. Nevertheless, these choreographies remain unseen - the

performance between materials is left to the viewer only as traces of

changes. It seems to me that you’d almost pick the ‘wrong’

tool just to radically experiment how an unusual interaction would change

the surface of things, or to explore how the friction would unfold the

substance and challenge the notion of essence. JW: What also stands out for me is the idea of the artist being located ahead of the work. I think Deborah touched on this positioning when she wrote that she is interested in provoking a series of events – to precipitate the process - without necessarily knowing the outcome. This location ahead is intriguing to me because it is the place I often find myself working from, as well. The sensation of physically making real a vague image or idea is like being further along than the work itself; as though I have already reached the place where the work is, and now must discover the materials and lines to give it a form. DM: Certainly

there are materials outside the more traditional art lexicon that are

waiting to be used, mined and explored. I don’t go intentionally looking

for them, but have never felt bound by one specific material I wanted

to stick to. Over the years the list of stuff I have worked with has

grown, but what has remained consistent, are the issues, some of which

we are addressing here. Janita, how did you decide upon concrete for

(some) of your sculptures? I find it is a material people either love

or hate (both artists and viewers). You? JW: I enjoy working with concrete because of its colour and weight. When

beginning these sculptures, I wanted something that replicated the city,

in its blankness that is not really a blank. In opening up my casts

I always discover pockets of air, rivers of subtle colour shifts, and

the minute detail of the surface of my mould. There are lines that cannot

be entirely straight. Concrete is a material that though it first

appears as impenetrable and permanent, it cracks and erodes just as

everything else. DM: I was challenged by the artist Stephen Schofield this year about my

putting my work on the floor, so I have been rethinking my insistence

on not using podiums. I am curious to know how you decided to

install your work that I am catching glimpses of through your documentation.

I love the idea of the reservoir as used in your print titles and its

manifestation in the images. I too have used it for an installation

I made once upon a time. It’s filled with associations. BM: I

am inspired by your remark of “axis turning” — I have been thinking

a lot about suspension and what it means to be suspended — does movement

always imply the existence of an axis? How does the use

of podiums relate to the idea of axis for movement and notions of time

and memory? I have the feeling

that podiums are often-unnecessary axis for directing movement around

a work/object: a suspension that directs the object into a specific

movement towards the viewer. Sometimes we need to prescribe this relationship,

but most often it is just fear and control taking over. JW: I did use sculpture plinths, but wasn’t entirely satisfied with the height. I haven’t resolved this. In some ways I like the supposed neutrality of a 3-foot podium, but of course it isn’t really neutral, and yes, I think the impulse to use it is based in a need to control the posture of the body, and the ways of seeing, more than actually opening the work up to other possibilities. What were the comments directed at your own placement of your Giant Okeydokes on the floor? DM: Comments

on the Okeydokes being on the floor were that they are at too

much of a distance from the viewer, do not engage the body enough, that

there is a role to be played by the podium or other such devices in

allowing the work to be closer to the eyes and the mid-range of our

bodies. I have spent so much time thinking about ways of presenting

work without such bug-a-boos that I am now actually curious about further

alternatives including what is the role a podium-like device can hold.

Last fall and onwards, the Okeydokes were exhibited in presentation

boxes I had made out of acrylic. I will send you both pictures when

I am home once again. Working with these presentation boxes allowed me

to stack them in columns and other configurations. They have now been

tried out in three different exhibitions and have led to other possibilities.

I have also sunk large magnets into them which allowed me to affix them

to walls, ceilings and onwards. Certainly their sense of gravity in

these various situations has been different, allowing for a better sense

of their orb-like form. But I still like the idea of someone bending

down and picking one up - which people do - or lowering oneself down

to the floor to see the work closer! Is this my being too much of a

control freak? Interestingly, when the work has been in straight lines

on the floor, children have felt very comfortable moving through it. Giant Okeydoke in acrylic casing, Deborah Margo Giant Okeydokes, Deborah Margo BM: I agree that the podiums already set a relationship - with the eyes - but they create a suspension and a frame, which is interesting when you say they are surrounded by acrylic, because it is a frame that doesn't isolate visually from the surroundings.

Deborah, you mention

your surprise when things remain and I’m thinking that permanence

and our inability to recognize things in their constant changes is connected

to our need for an essence of things. The idea of casting a shadow

addresses this question, in my point of view. A shape created by cast

light originates as an object. It is not the light anymore, but

the trace of a trace: the permanence of a constantly changing ‘thing,’

trapped into a permanent shape. Photographs of Light, Bianca Scliar Mancini, 2010. JW: The density of marks in the broken link you encountered, Bianca, reminds me of Agnes Martin’s grid paintings. Here again I feel as though there is both a fullness and an emptiness, working together to describe the indescribable. We give form to the formless, always working on the edge of something that can’t quite be written about, can’t quite be drawn, captured, shown. But we can give an impression. The container gives shape to an inside and an outside. Lines create borders between something and nothing. DM: Agnes

Martin. I have such respect for her work although it is very different

from where I come from. There is a search for perfection that is far

away from the messiness of daily living which I deeply love and wonder

about. You see the "messiness" also has such a vital presence

in art and I don't want to deny it – it’s what makes things feel

alive. But I also love the moments of contemplation that Martin

offers. BM: Janita,

the drawings from your Spacious Object project are so elegant

- they remind me of Bianca Tomaselli, a young Brazilian artist’s,

work. Maybe because of the straight lines and the cleanness of

the shapes, but mostly because you both revert the principal of constructivism,

each in your own manner. Tomaselli raises the feeling of impossibilities,

since she draws with hair and a straight line is never a perfect line

- it is almost like setting yourself up for an impossible task. Gardening

is also about this effort of arranging and combining forces of nature,

of nurturing, playing chess with the responses and with chance. You,

on the other hand, by playing between two and three dimensions (evoked

by Deborah when writing about shadows) construct lines that are organized

in such a way that instantaneously become containers: the essence of

bordering and holding, and giving shape to whatever matter that otherwise

would leak, formless. If you can

put your five fingers through it, it is a grid (Study 1 and 2), Hair on Fabriano paper, 7x5”, Bianca Tomeselli, 2008. Gardening DM: For

the past six years I have been working in the summer as a gardener.

This year I have more than twenty clients and am working outside steadily

from mid-April (when classes ended at the University of Ottawa where

I teach part-time) until the end of August. The smallest gardens have

been planting pots or tending to a small strip outside a condo project

whereas the largest are elaborate gardens situated next to the Ottawa

river. Some are of my design, others are tending to someone else’s.

I am immersed in plants and their changes, though I don’t think this

can be called nature. Gardening is about making all sorts of environments

– installations? – following different clients’ needs. Artifice

and artificial, most certainly. Yet the cycle of plants does belong

to nature. Seeds have germinated or root systems have revived. Some

I have helped along, a great many have their established cycles taking

pretty much care of themselves. We have passed the mid-summer point

and I can already see the signs of the growing season moving along to

its inevitable end, returning to dormancy. Life/death/life/death… They

are part of the same thing, not macabre, just a fact whether I choose

to pay attention to it or not. And for me that is the point – wanting

to pay attention (for lack of better words) to what is going on right

in front of me. The images attached

are from one of the gardens I’m working on. Erich is a pack rat of

the severest of kinds, yet he has asked me to reclaim a garden strip

at the back of his yard in an Ottawa suburb. The plot I’m working

on is about 2.5 meters by 25 meters and is reached by a narrow path.

Every week, since May, I have worked a couple of hours, discovering

all kinds of perennial plants that have been spreading for many years,

clearing spaces for the ones I’m selecting, adding new ones. The over

growth and embedded objects are a challenge – should they be left

as is or “cleaned” up? What is the balance between my supposed civilizing

and letting things just be? What is a weed? What is a desirable plant?

And what about the tree seedlings Erich has let grow rampant, yet he

claims he wants to have a lawn again! Erich’s garden, Deborah Margo, 2010. JW: The

challenge you talk about regarding Erich’s garden reminds me of the

process of making art, too. How much control do the materials allow

you to have? How do you know when you have reached the point when you

should stop working? Are the saplings that grow up the birth of something

new, or just a remnant of an old thought that needn’t be kept around

anymore? I have attached

a collection of images (mushrooms, kale, succulents) that relate to

Deborah’s Giant Okeydoke series. There is something grotesque

about these disintegrating balls of sugar, but also gorgeous. In their

state of decay the jawbreakers remind me of things growing, expanding,

opening. Collected Images, Janita Wiersma DM: I am intrigued by the plant images you have collected. Are some

of them pictures you have taken, others you have found? There is the

mundane – the fall tomatoes, the kale and broccoli, as well as the

more exotic (in this part of the world, anyway) of the fungi and the

living stones. It is so curious

that you have made a link between gardening and the Okeydoke series – so do I. Something small but fantastical. Also something

still changing. They are ephemeral works. I don’t know how long they

will last, though the hardened sugar has stuck around longer than I

expected. Still, it easily reacts to water/humidity, potentially continuing

to “bloom” and “cloud” over, though the lacquered, sanded surfaces

have stayed clear so far. JW: The mundane images, as you say, are ones I took myself at my parents’ farm in Southern Ontario, the rest I have collected from other sources. Yes, it’s the slow pace of things growing, as well as the spectacle of plants seen up close that refers me back to the Giant Okeydokes. Growth can seem so slow but then suddenly the plant has become something else entirely. I imagine the experience of looking at the jawbreakers evolve over time is a similar process of discovery - time manifest in remarkable points. Community BM: Deborah,

I would be interested in hearing about your community-based projects

and other sorts of collaborative practices and how they relate to my

seeing you as a provocateur of relations between bodies/materials.

I would like to learn from you about the one big question that’s been

chasing me lately: when and how do these practices become an artwork

and when do they remain in the realm of experience that informs your

perception as an artist, but are not directly art? When does gardening

conform to an art practice, or a piece, for example? What is the role

of the artist in relation to community and social issues? Should we

be more responsible than a dentist, for instance? DM: I

have worked on a number of collaborative projects over the years and

enjoy doing so every once in awhile. They are tough to do and demand

great amounts of trust with those involved and the possibility that

there will be no final outcome or so-called result. Generally, the conversations

and the sharing of ideas are what I find the most exciting and intellectually

nourishing. The most recent project of this sort was with Devora Neumark

(Why Do We Cry? Lamentations in a Winter Garden - there is a

fair amount of information on it if you look it up on the net.) For

me, I would say this project was definitely pulling on various definitions

of what is art and put me on very shaky ground in my thinking. Having

work at the Toronto Art Fair at the same time was a travesty in terms

of different contexts! In Toronto, the convention center was filled

with acres of objects that would be called “art” at the same time

as there was an economic melt-down, while in Montreal I witnessed the

local “residents” in various states of deprivation who were also

an important part of the group participating in the project. I think

my experience of the project and Devora’s were completely different.

To date it has made me turn once again to object-making and yet I continue

to question where my work belongs, and this at a time when I have had

a fair number of experiences showing in a variety of so-called art contexts

i.e. commercial galleries, public galleries, artist-run spaces, independently

organized projects in non-art spaces… Another community

project in which I grew scarlet runner beans over the course of six

months was in the realm of art practice. Nevertheless, I think a lot

of the gardening work I do does not conform to the conventions of an

art practice. And yet there are other parts that seem to fit perfectly

i.e. the notion of different parts and their relationships mattering

far more than single works or gestures; the attention to context being

paramount; the notions of change we have been talking about since the

beginning of our conversation; how one moves amid or through an art

work. Gardening helps me with the installations I make / the installations

I make help me with the gardens I work on. Yesterday I visited

a sculpture exhibition taking place in Confederation Park here in Ottawa.

All very laudable goals having to do with recycling of materials considered

by a group of mid-career and emerging artists, yet the work was terrible

and the presentation of it even worse. I had to think what made it so

bad, when the written descriptions spoke of such terrific intentions.

All of the work sat on dead grass and was set out in a perfunctory fashion

with about the same amount of space measured out between each work.

It’s the old story of things speaking rather than doing or “I am

telling you what I am about rather than evoking something for you to

experience if you so choose” while not addressing where they were

placed or shown. The sculptures did not do well “out in the world”,

so I have been thinking what would allow them to be outside and resonate.

I saw one of them on the roof of a car today with the vehicle moving

through town – this was already a great improvement. And this brings

me to your question of what is the role of the artist in relation to

community and social issues. Though I have started working on another

community project here in Ottawa, I am still ill at ease with the role

of the artist in such a context. Once again, the group conversations

on the possibilities for a project on food production have been terrific,

but I do not where all the wonderful talk will go. Are we another group

of do-gooders? Are we feeling guilty about the old myth of art’s lack

of function in a world of accountability? Is there a link with the other

projects that I have been talking about with you and Janita? Does there

need to be? What do you do with the notion of art being an elitist undertaking

unless it is based in a community practice? I am wary of such dichotomies. The dentist provides

a specific service for their clientele. When I garden I also provide

a particular service that is usually set by the client’s needs. An

architect’s work is also most often bound by such a relationship.

Art-making has the possibility of being in a different realm. When I

am working in the studio I am most often researching possibilities of

different issues or problems I am curious about. I do not know the outcomes,

but I know I am working towards finding something. Investigation? Something

akin to being in a laboratory? There is a need for results somewhere

along the way and these I eventually choose to share outside the studio.

The opportunity of this conversation allows me to know these issues

are not mine alone, but are also shared with others including the two

of you. In fact, there have been multiple points of connection which

I love. I think I have

come closest to understanding my responsibility as an artist when I

am in a teaching context. I have a certain set of experiences that can

be shared with others and in that sharing students will interpret them

according to their own needs. I do not teach to have students necessarily

become artists rather I hope to have them learn more about what it means

to think creatively. I do believe this notion can be applied to anything

one does. How do we problem solve? How flexible is our thinking? Are

we able to consider an argument from a number of points of view? What

happens when good or bad/I love or I hate are irrelevant? What allows

the dentist to strive for the best at what they can be and do? JW: I don’t have much experience working on community based projects as

an artist. I’m involved in community in many ways, but I don’t participate

as an artist necessarily. Or I do in part, but not with the goal of

a completed project at the end of the process. The questions that have

come up around the role of the artist are definitely ones that I consider

as well, especially when preparing to mount a show. What is my responsibility?

The gallery space is a difficult one for me because it can be such a

place removed but I also love it for the remove it can provide. I suppose

this question about the role of the gallery is very similar to the discussion

we have had about how to use or not use plinths for display. I think

my sense of responsibility as an artist is no different than the responsibility

I feel as a person in the world. I don’t want to alienate people or

make them feel unsafe. I aim to offer a space that is open enough that

many ways in and out are possible. Much like a conversation, I hope

that ideas and points of connection proliferate. I am still turning

over this question of role and responsibility and how actions spill

over into art. Memory / Traces BM: I

would like to think about where do we place ourselves in this process

of trying to reach time and its traces. Are we located always ahead

the setting that is observed? This is where I think Deborah’s work

differs from ‘remembering’: it is about memory but placed ahead,

looking at the body of things and how they survived the flow of time.

How do you see your work enunciates qualities of memory? What are the

relations you seek between that which remains and the invisible, the

potentialities? Where are you

in this flow of time and change? Have you ever showed the procedures/performative

interactions between materials in a gallery setting? I am intrigued

with the allusion to emptiness, because of the nature of the gesture

of constantly capturing change. Where is emptiness or void? Isn’t

vanishing instead of a synonym for disappearing, closer to changing: transduction? DM: Good

question about where am I in the flow of time and change in the situations

I set up. I do take some responsibility in provoking a stream of changes

in the sugar and salt works and also have some control over when they

can come to some point of stopping or freezing in their deterioration.

Inevitably the work will return to being dust one day which I am fine

with. I don’t take much stock in the permanence of art works. Not

much of a surprise there, I guess. Yes, I have been interested in the

procedures/performative interactions being made more public. I have

made preliminary designs where a sugar ball /okeydoke would be slowly

transformed in a gallery setting, but so far none of the spaces where

I applied to show such a project have bitten! A slow stream of water

would bathe the ball of sugar and collect again below it, forming a

new work. Eventually the original form would no longer exist, but its

residue would become something new. I have also grown scarlet runner

beans on structures/supports made from what I found in the garbage and

am often in conversation with people living in the surrounding area

commenting on the growth of the plants over a period of six months. I’m not sure I believe emptiness

is really possible. Transduction –

what does this mean? I would understand it as a process where one type

of energy is converted into another. We may not see it with the eye,

but we nevertheless know that it exists. Not surprisingly, this does

interest me greatly. Energy is a constant - it is a question of what

shifting forms it takes. BM: I am referring to transduction as it occurs in Gilbert Simondon’s work. According to Andrea Oliveira, who has been writing recently on Simondon: “Transduction is a chain transformation between participants from the same system, from the same associated milieu, which can occur in a micro or macro molecular level. It takes place within participants who previously find themselves connected within a system, whom, as the transformations occur and propagate, are changed. In other words, changes that re-conform the constitutive participants themselves. Such a chain transformation is structural and composes the operating mode of the system, in return. According to Simondon , ‘for transduction we understand an operation which is physical, biological, mental, social, through which an activity is propagated gradually in the interior of a domain.’ 1 Transduction processes extrapolates the closed unity in itself and it’s identity. Simondon explains that in the process of individuation occurs a series of transductions, a progression through which the individual is revealed, but also the milieu that constituted it. It conforms a mode of production within the individual, which produces an actualization of that which is pre-individual. Art, in this context, proposes a non-deterministic mode, as if within the individual surroundings was a reminiscence of a pre-individual reality, associated to the individual, a reality that would rebound the singular with the collective. Transduction, contamination, propagation, something in formation as a continuous collective operation.” JW: This is why I love the idea of casting the drawings of captured light – I am becoming more and more interested in the idea of pushing things to their limit so that they almost spill into their opposite. Already the paper shapes you mentioned that capture the light are only a representation of the movement you were tracking. I can imagine how creating three-dimensional blocks of these drawings would provide them with a further dumbness, but perhaps also a deeper voice, simply because the opposite is always there, in everything. BM: I

am also struck by the attempt to collect traces of time passing. In

the casting series it happens in the scale of a day - so, at first you

are the one marking the points where sunlight draws shades at the window.

After you leave, it is the sun, again, that will highlight each mark,

striking the different drawings along the day. The event, which was

marked at the walls will never have the same shape again, even, and

one can notice the slight differences once the sun hits the drawings

on another day. Usually when we

evoke memory it refers to an event as a static circumstance, something

we lived, but which remains behind and that we re-visit mentally - or

re-collect. I see in your procedures something different: what does

remain? How does it link to an origin of forms, or transgress what we

thought to be an essence of the material? I would like to

provoke you and ask about whether you understand your practices as time-capturing

procedures? JW: I love the idea of time-capturer. In Deborah’s work the net is cast

wide and what is caught is a process of disintegration - transduction

- that occurs so slowly that it almost appears to be immobile. A moment

is captured, but it cannot be held because the third, this middle force,

urges the process onward. BM: Although

I see the attempt to display that what remains, it is the opposite of

claiming for an essence of things (which I mentioned in an earlier correspondence).

It is only the abilities to give, to let parts of it dissolve that allow

some force in the middle to emerge to the surface (an interior axis?).

Memory, in this sense, is about physical modification and not recollection

of a set of circumstances. DM: I

agree with your definition of a memory and its evocation, but I am not

certain it is of static circumstances. Rather it is a gathering of moments

that for some reason we have deemed important to us. Some see the memory

as an exaggeration or a fiction, but I am not convinced. Certainly it

is selective. I have lived with the same person for close to thirty

years and what he chooses to remember and what I do, about the same

circumstances, is completely different. And yet I also know, based on

experience, that many of my memories of particular individuals – their

smell, the sound of their voice, how they hold themselves – are more

accurate than I thought possible. Sometimes these memories have shocked

me in how they have sustained particularities of another person when

I see them after many years. Yes, I am interested

in how the event changed the body or object that experienced the event

– it remains the same, but also different. A summation of its original

manufacture, how it has been changed and yet continues to exist. I am still working

on understanding what you mean about being located ahead of the setting

it is observing. Do you mean the work anticipates its own changes before

they happen? Perhaps not, but I will wait to hear back from you, Bianca.

I do hope for a conversation between the materials I choose, the stress

they undergo and my decision-making – a series of events that I try

to precipitate without necessarily knowing their outcome. Eventually,

when it becomes endlessly predictable, I move on. This came up in a

lecture I participated in last year with the artist Eric Cameron. He

is satisfied with repeating the same events over and over again for

years on end, while also not knowing the form of the outcome, yet he

sticks, pretty much, to the same materials (paint and gesso). I think

I am more restless. What was there.

What has changed. What has become. All three states are co-dependent. BM: I am

curious: Can your sculptural pieces be touched, manipulated by the audience? DM: Three-dimensional

objects most often ask to be touched. I, for one, tend to understand

a great deal about the world through my finger tips. As always, whether

someone chooses to touch my work will largely depend on the context

where they meet it. Once a series of sculptures I made were set up on

casters; every time I would visit the gallery, all of the work had been

moved by the audience despite there being no sign inviting them to do

so. I tend to take the audience’s manipulation of the work as a sign

that they have been interested in it, despite when they have been admonished

by a security guard or gallery owner! I am sending here some images

of recent work: large salt lick blocks that have been immersed in water

for varying periods of time. Salt Licks, Deborah Margo, 2010. Salt Licks, Deborah Margo, 2010. BM: These are so beautiful!

What are salt licks? The image of corrosion is such an interesting

way of, once again, framing time and memory. DM: Here is a definition about what a salt lick is, straight from the internet: “A salt lick

is a deposit of mineral salts used by animals to supplement their nutrition, ensuring that they get enough minerals in their diets. A wide assortment of animals, primarily herbivores,

use salt licks to get essential nutrients like calcium, magnesium, sodium, and zinc. When a salt lick appears, animals

may travel to reach it, so the salt lick becomes a sort of rally point

where lots of wildlife can be observed. Farmers have

historically provided salt licks for their cattle, horses, and other

herbivores to encourage healthy growth and development. Typically a

salt lick in the form of a block is used in these circumstances, and

the block may be mounted on a platform so that domesticated animals

do not consume dirt from the ground along with the necessary salt. Salt

blocks for farm animals can also be treated with medications, which

may be convenient when someone needs to medicate shy animals, or a large

group of animals. Some people

also use artificial salt licks to attract wildlife such as deer and moose,

along with smaller creatures like squirrels. Animals may be attracted

purely for the pleasure of the humans who install the salt lick with

the goal of watching or photographing animals around the salt lick,

and they are also used by hunters to encourage potential prey to frequent

an area. Wildlife biologists may use salt licks as well, to assist them

in tracking populations, and wildlife salt licks can also be medicated;

deer, for example, might be fed birth control to keep them from proliferating

in areas where there are few natural predators. The universal

popularity of salt licks with a wide range of animals illustrates the

ways in which wildlife naturally seek out nutrition which is essential

to their survival. Salt licks can also provide nutrition for predators,

in the form of conveniently-located prey who may be distracted by the

salt lick long enough to become a snack.”2 Are you okay with

art works being “beautiful”? Today, often in contemporary art, I

find it has become like a four letter (swear) word, something to be

embarrassed about, an insult, or having a subversive connotation. Strange.

I understand your use of it being something else altogether – that

it is possible to be visually attracted to art works and this is a positive

experience. It is not what I look for necessarily when I look at other

works, but I believe it definitely has its place. It can act as a lure

for an art experience to unfold into further connotations, associations,

meanings, other possibilities. Yes, that would be my hope in making

something beautiful. JW: The

transient way that the Okeydokes, salt licks, and even the Light-Earth Drawings capture a moment seem very much akin to memory

for me. I agree – memory is not static, but rather a process that

occurs in the present. We don’t return, we create anew with threads

of thought that have moved with us all along. In Deborah’s work the

gesture of adding water is a memory in process, continually renewing

itself in the present moment. We had milking

goats when I was growing up and there was always a maroon salt lick

in the corner of their pen that we used to check up on to see its progression

from square to pock marked form (and sometimes to steal a taste). The

goats would slowly carve the block out with their rounded licked hollows

– it was a beautiful object especially set as it was on an overturned

pail in a pen strewn with straw. The process I watched the goats engage

in reminds me of the project Gnaw by Janine Antoni where she

shaped a block of chocolate (and one of lard) with her mouth. Clearly

for the goats this is an instinct to gather nutrients from the block

to thrive, and perhaps the same can be said for the impulse to create

art – it provides the opportunity to thrive. DM: A wonderful summation touching on many of the issues the three of us

have been writing about. Many thanks for this, Janita. Also thanks for

bringing in Janine Antoni’s work. I am very grateful to both of you

for the conversation we have been having. JW: Thank you both for

all you have said - I have enjoyed this conversation very much. BM: Thank you both for

the inspiration. Notes Simondon, Gilbert. A Gênese do Indivíduo. In: Cadernos de Subjetividade – O Reencantamento do Concreto. São Paulo: Hucitec/EDUC, 2003, p.112. Free translation |

>> Table of Contents edited by B. Mancini, J. Weirsman Healing Series Brian Knep 276-278 R.U.N.: A Short Statement on the Work Paul Gazzola 279-282 Castings: A Conversation Deborah Margo, Bianca Scliar Mancini and Janita Wiersma 283-308 Matter, Manner, Idea Sjoerd van Tuinen 309-334 On Critique Brian Massumi 335-338 Loco-Motion Andrew Murphie 339-341 An Emergent Tuning as Molecular Organizational Mode Heidi Fast 342-358 |

||||